Legislating in Utopia - why the "safeguards" in the Assisted Suicide Bill are not what they seem

The question is not "do you believe in assisted suicide?". The question is "do you trust this bill to get this right?".

Introduction

Utopian legislation is almost always dangerous, and it is certainly literally so in the case of assisted dying.

Responsible legislating demands MPs face the reality of the world we live in, rather than dealing only in best case scenarios. We do not live in a perfect world; we live in a human world more than replete with human fallibilities. We live in a world that developed the civil law concept of “undue influence” which allows courts to undo superficially lawful gifts and transactions where manipulation and exploitation are at play. We live in a world where the offence of controlling and coercive behaviour is prosecuted to protect people in abusive relationships. We live in a world where the Fraud Act 2006 created a specific offence of “fraud by abuse of position” to deal with criminals who exploit their position of trust over the vulnerable for gain. It is because of those realities that the question we must ask of the assisted suicide bill is not “do you believe in this policy in a perfect world” but instead “do you believe this law work without error?”. For the reasons I will explain below, my view is that this bill comes nowhere near to addressing these serious matters, it is a bill drafted with utopia in mind and it seems, in deliberate ignorance of the realities of the fallible world in which we live.

Clauses 1-2: Who dies?

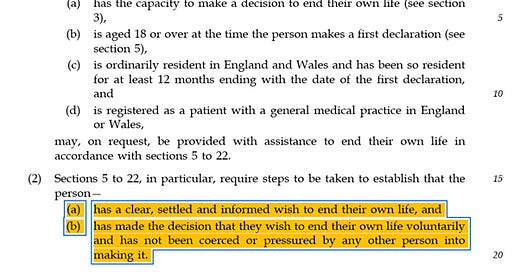

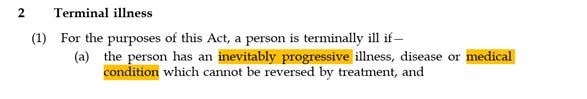

By clause 1(1)1 assisted suicide is open to a terminally ill person with capacity. A person is “terminally ill” as defined by clause (2) if they have an inevitably progressive illness, disease or medical condition and their death can reasonably be expected in 6 months. By clause 2(3) a person is not terminally ill “only” because they are disabled or mentally ill2. In addition, the request for assisted suicide must satisfy the two core requirements of the bill in clause 1(2)(a) and (b), namely, the person must have a “clear settled and informed wish to end their own life” and they must have “made the decision voluntarily” and not have been coerced or pressured by any other person into making it.

You may think on the face of it these sound like robust and adequate safeguards and I would concede they certainly have that appearance on first reading, but the reality is somewhat different if one considers the following points:

I begin with a hypothetical scenario to make my first point. Person A suffers a debilitating and serious eating disorder. She has been hospitalised on a number of occasions and her illness is now being described by medics as “treatment resistant”. It is said she is in the “terminal stages” of anorexia3. She refuses to eat and thus the doctor determines she has less than 6 months to live. She has capacity for the purposes of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 but is refusing any treatment. Her doctor says “Anorexia nervosa carries a guaranteed medical cause of death from malnutrition should weight loss continue unabated. A prognosis of less than six months can fairly be established when the patient stops engaging in active recovery work.” Person A does not engage in any such work and her physical health reaches a the status of a medical condition which is inevitably progressive (as required by clause 2(1)(a)).

Person A says she has a clear, settled and informed wish to end her own life and she said she has not been coerced or pressured. The position is that Person A will qualify under this act because (1) she satisfies the prognosis criterion and (2) while she has a mental disorder within the meaning of the Mental Health Act 1983 (see screenshot of the bill below), this is not the “only” reasons she is terminally ill because there is now associated physical deterioration. For an informed discussion on this issue, see the work of Fiona Mackenzie MBE and eating disorder recovery expert Chelsea Roff on Youtube here4.

The result is that person A dies by assisted suicide in consequence of their eating disorder, as has been the case in many other countries.

Eating disorders are by no means the only example of where drawing a clear line between mental and physical health is difficult, if not impossible. Serious substance misuse, mental health conditions characterised by serious self harm and disabilities with associated progressive deterioration in physical health might all in principle qualify under this bill.

Second point. The bill states that suicide may be assisted where a person has an inevitably progressive illness, disease or medical condition and their death can be reasonably expected in 6 months. Many doctors have opined that such prognoses are difficult to make with any certainty and that even the most qualified and professional among them will admit to some guesswork in coming to what is, on any view, a very difficult prediction to make. It is also true that medicine moves on, sometimes quickly, sometimes unexpectedly, and so situations can change rapidly. There is clear evidence of just this in the case of a proponent of this legislation, Esther Rantzen, as reported by the Independent on 19th September 2024 under the headline “Esther Rantzen reveals lung cancer ‘being kept at bay’ thanks to new drug”. The report continues, “Dame Esther Rantzen has revealed her cancer is currently being “kept at bay” thanks to a new drug. The 84-year-old broadcaster, who has terminal lung cancer, said she is feeling “much better than she thought she would be” thanks to a new drug she has been taking.5”This example, and many other cases demonstrate, that while there are clear cases where 6 months or less as a prognosis can be predicted with confidence, there are also a category of situations (even with routine diagnoses) where this is not the case.

There is every reason to anticipate that activists groups will try to widen the scope of who qualifies for assisted suicide because:

All legislation must be read in such a way as to comply with the Human Rights Act of 1998 and some groups will argue that the “right to suicide” is one that should not be restricted by the 6 month prognosis,

Activists have indicated that they intend to mount such claims and;

The committee appear sympathetic to that argument as demonstrated by the fact they will be hearing from retired High Court Judge, the Hon. Sir Nicholas Mostyn (who has Parkinson’s and believes the category of eligible persons should be much wider and include “intolerable suffering”).

This broadening of categories might happen at committee stage, or that objective may be prosecuted through the courts. I would argue that once the principle of assisted suicide is good in law widening is inevitable, what started as “6 month to live” could very easily become “quality of life” because this is what happened in the US and Canada with rights based arguments.

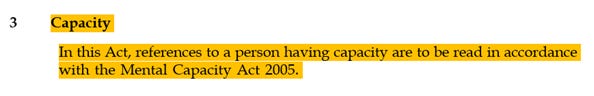

Clause 3 - Capacity to decide

By Clause 1(2)(a) a person requesting assisted suicide must have a “clear, settled and informed wish to end their own life” and by Clause 1(1)(a) they must have the capacity to make a decision to end their own life. Capacity purports to be defined in the following way:

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 regulates legal and care arrangements for people who cannot make their own decisions, it is frequently encountered in safeguarding work for those with dementia and it established the Court of Protection to rule on cases according to an assessment of the best interests of the person concerned. When the court makes judgments about best interests, it will often hear from AHMPs (Approved Mental Health Professional) and other experts on the question of what capacity a person has. This can be a very complex issue, some people have fluctuating states of capacity, sometimes experts can disagree and sometimes a person can exhibit some, but not all of the qualities of having6. Section 2 of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 says that a person lacks capacity in the following circumstances:

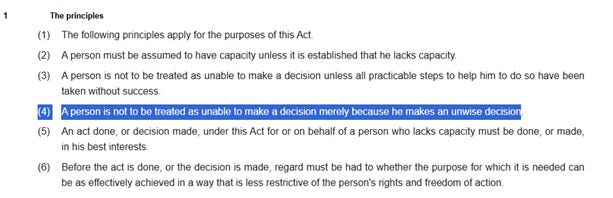

Section 2 tells us when someone doesn’t have capacity, so we can reverse the position from section 2 and summarise when someone does. Conducting that exercise the basic position in law as this - a person has capacity where they are able to make a decision for themselves and they do not have an impairment or a disturbance in the functioning of their mind or brain. This basic definition then has to be read in light of the “5 principles”. These are a set of overarching statements in section 1 of the Act that govern how it is applied, here they are (emphasis added):

By section 1 (4), we can see that one of the principles is that a person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision merely because he makes an unwise decision. This is self-evidently an important point when discussing a decision to unwisely seek assistance with suicide.

It is worth pausing at this point to reconcile the capacity provisions with Clause 1(2)(a)’s requirement that a person requesting assisted suicide must have a “clear settled and informed wish to end their own life”. Reading the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and the text of the bill together we can see that an unwise but “clear settled and informed wish to end their own life” would be, in principle, lawful.

That might strike you as counter initiative and potentially dangerous, particularly in the cases of depression falling below the clinical standard for diagnosis, substance misuse and general mental health conditions falling below the (very high) standard of a “mental health disorder” in the 1983 Mental Health Act because these states might easily give rise to situations where vulnerable people make unwise decisions.

Let us now focus on one of the core concepts of the bill, the “clear settled and informed wish” to end your own life and ask what that means in law. The meaning of these words matters, yet clause 40 of the bill which is concerned with “interpretations” and defines a number of other terms in the bill tells us nothing about what these words should mean in law. This gives rise to a number of reasonable questions about what exactly these words mean;

How clear is clear? If a person says “it would be better for those around me if I wasn’t a burden”, is that sufficiently clear for the act? If a person says “on balance, I want to commit suicide with the help of a doctor”, is that clear enough? If a person says “I’m just so depressed, I want this all to end” is that a clear statement? How about “I’ve had enough of this”, how about “I’ve had enough” and the patient is 20 with a history of depressive disorders and substance misuse. Is that “clear”?

How settled must the wish be? Do a few changes of mind in the past matter, would they make a wish “unsettled”? What length of time constitutes settled? Would it be alright for different doctors to take different views on what is settled and what is not? Can a person cancel their declaration they wish to commit suicide (permitted by the bill) and still achieve settled status in the future? Or would cancellation mean achieving “settled” status was impossible?

What is an “informed wish”? How informed? What sort of information are we talking about here? Must the person seeking assistance with their suicide be informed as to the lethal substance they are to take and the effects? About side effects should the substance fail? Are they to be assessed as to how informed they may be as to palliative care options? What precisely is the character of the wish that needs to be “informed”? Do they only need be informed that they are taking a suicidal decision?

The bill is entirely, and unforgivably, silent on these questions.

The imprecision on what the words “clear”, “settled” and “informed” mean offers very little assistance to doctors who are expected to certify the capacity of suicidal people against those three words. It is not clear on the face of the bill what those words should mean in law and therefore how doctors should measure such wishes in law.

It is worth considering at this point what sort of doctors might be asked to undertake such a task. Looking ahead in the bill, we learn that the capacity assessment is not to be carried out by an Approved Mental Health Professional or psychiatrist, because clause 5(3) permits any “registered medical practitioner” (which means any doctor registered with the GMC, so just about any doctor) to do so.

The clause quoted above is concerning because it leaves open the question of what training, qualifications and experience will be necessary for the doctor assessing the capacity of the person articulating suicidal ideation.

The bill simply dodges this question via clause 5(3)(a) and hands responsibility over to the Secretary of State to sort that out later, only this isn’t a cast iron requirement that this actually happens because the bill states that this “may” rather than “must” happen.

The worst case scenarios are all too predictable here. As the bill stands, a GP with little experience in capacity assessments could be nonetheless asked to conduct such an assessment and to certify that a patient has a “clear settled and informed wish to end their own life” with no guidance as to what those three crucial words actually mean.

Further, a GP who took the view that such a wish was unwise would nonetheless be forced to conclude the person still had capacity as this is a central principle of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. We have no idea on the face of this bill what training, qualifications or experience might or might not one day be required by the Secretary of State and so the bill asks us all to take on trust that everything will be alright further down the line once this radical change becomes law. Passing the buck to various Secretaries of State to come up with safeguards later on is a hallmark of blank cheque legislating and hardly inspires confidence that this issue is being taken seriously.

The risk is that the untrained lead the unwise based on undefined criteria.

Clause 4: Doctor suggested suicide

Clause 4 of the bill is perhaps one of the most fundamental proposed changes to the normal doctor/patient relationship in the form of clause 4 (2) which permits a doctor to raise assisted suicide where they consider it appropriate according to their professional judgment.

Many will consider this a fundamental subversion of the Hippocratic oath and have any number of objections about why and when such a suggestion is made. Supporters would no doubt point to clause 4(4) and say that any doctor making such a suggestion must also discuss alternatives. They may well do so, but reality is reality.

The fact of the matter is this. Realistically speaking, any doctor bringing up assisted suicide would more than likely have considered and discounted the effectiveness of further treatment and palliative care. This means that the statute mandated discussion can reasonably be viewed as a checklist/window dressing around a “suggestion” that is, in reality, a recommendation.

My observation is a more basic one. I ask this, what is meant by the exercise of “professional judgment” and “appropriate”? A doctor opposed to assisting the suicide of her patients would in all circumstances no doubt always recommend palliative care.

A doctor in favour of assisted suicide might, by contrast, recommend it as a matter of course. Both are professionals. Both exercise professional judgment, but both have radically different view on what is and what is not “appropriate”. A recommendation for assisted suicide is thus not so much a matter of “professional judgment”, because two professionals can reach different honestly held views, but instead is an articulation of a political position, because political positions among doctors, like all people, will differ.

The gravamen of my complaint is this. It is wrong to dress up political positions as “appropriate” “professional judgments”. The fact of the matter is any doctor raising this matter is politically in favour of assisting a patient in their suicidal ideation. That is not a professional judgment. It is not a matter of being appropriate or inappropriate. It is a judgment. A political judgment. To dress it up otherwise in statutory language such as this is a mannered fraud where plausibility is the desired benefit of the deception.

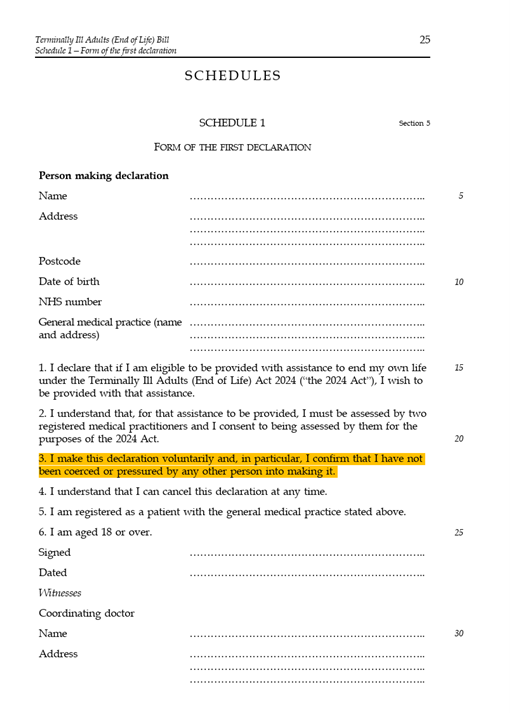

Clause 5: The first declaration

We will see in due course the act requires two declarations to doctors and then an application to the High Court. Clause 5 deals with the first declaration by a person seeking assisted suicide. It must be witnessed by a doctor, (perhaps one who suggested assisted suicide via clause 4) and one other person who cannot be a relative or someone who might benefit from the death7. The act provides for the form of the declaration in schedule 1 by way of a markedly simple and sparse form:

Readers will note that the person seeking assisted suicide self - certifies the absence of pressure or coercion. Many will consider this remarkable, certainly anyone who has any experience of undue influence claims, coercive control cases or fraud by abuse of position will note a quite obvious issue here. “Con tricks” have that name because the dupe is brought into the confidence of the fraudster. The undue influence remedy is often claimed by those who have spotted someone close to them being exploited. Victims of coercive control are often subject to “gaslighting” and convinced that abusive behaviour is either not happening or is a product of their own mental instability. In all these cases one matter is consistently true - the victim is the least reliable person to recognise or report abuse or pressure precisely because they are subject to abuse, pressure or manipulation. Exploitation can take many sometimes very subtle forms. The words of Lord Justice Lindley in the seminal undue influence case of In Allcard v Skinner (1877) LR 36 Ch D 145 are relevant here (emphasis added):

“What then is the principle? Is it that it is right and expedient to save persons from the consequences of their own folly? or is it that it is right and expedient to save them from being victimised by other people? In my opinion the doctrine of undue influence is founded on the second of these two principles. Courts of equity have never set aside gifts on the ground of the folly, imprudence, or want of foresight on the part of donors. ... On the other hand, to protect people from being forced, tricked or misled in any way by others into parting with their property is one of the most legitimate objects of all laws; and the equitable doctrine of undue influence has grown out of and been developed by the necessity of grappling with insidious forms of spiritual tyranny and the infinite varieties of fraud.”

These words are as true today as they were in 1877. Fraud happens. Abuse and exploitation happens. To often it happens to the elderly and the vulnerable. To often it happens to persons who might not see it for what it really is. Too often it happens to people who are exploited and depend upon their abusers or those who seek to trick or mislead them. Any person subject to such coercion offers us very little in the way of meaningful evidence by simple signing a short pro forma at the back of a statute saying that this is not the case. The only meaningful way such a claim could be tested would be by proper and wide examination of all the surrounding evidence to establish in truth whether or not someone was genuinely exercising free will or not. Which brings us to clause 78.

Clause 7: The first rubber stamp

Clause 7 of the bill introduces a fundamental problem we will encounter again and again in this bill, it requires doctors to certify a matter they cannot possibly be certain of. By clause 7(2)(g) the first doctor must ascertain whether the person seeking assisted suicide “made the first declaration voluntarily and has not been coerced or pressured by any other person into making it”.

This clause should be read together with clause 9 which requires that the doctor, “examine the person and their medical records and make such other enquiries as the assessing doctor considers appropriate”. The words “other enquiries” are not defined, nor is it clear generally what enquiries the bill envisages that doctors make.

This section has rightly been the focus of some rather obvious concerns which can be summarised as follow:

Nowhere in this legislation do we even begin to understand how a doctor is supposed to satisfy themselves that the person seeking assisted suicide “made the first declaration voluntarily and has not been coerced or pressured by any other person into making it”. We know that the person in question made the declaration and signed the form, but we don’t know anything about vast personal, financial and emotional hinterland behind that decision. Strikingly, in my view, the doctor has no powers in law to call for or consider financial evidence. A person could, in theory, have changed their will in favour of a fraudster pressuring them to end their own lives the day before the “first declaration” and yet (1) a doctor would be unware of this fact and (2) no party seems to be under any obligation to bring that to the attention of the doctor. You might think that responsible legislators would consider measures such as that in money laundering laws which requires banks to off the police to strange transactions. You might think that a doctor should be at the very least be appraised in full of the financial implications of a person’s death. You may also think asking doctors to even consider such questions in the first place is beyond their expertise.

There is no requirement here for a “SAR” (A Safeguarding Adult Review). There is no requirement for an Approved Mental Health Professional to conduct a social work style report setting out the familial and social background of the person seeking assisted suicide . The for itself doesn’t tell us why the person is seeking suicide. These are self evidently concerns of an extremely serious character. The bill requires a doctor to sign off a statement they could not possible know to be true. To require this of doctors in the first place is extraordinary, for they have no formal training in detecting or proving undue influence, but in the second place to ask them to do so with none of the tools the police or courts would use to detect fraud/undue influence is, frankly, extremely dangerous.

It is worth remembering that undue influence/fraud is often insidious and can be difficult to prove. In an undue influence claim, the Claimant often has to piece together myriad sources of evidence to show the court that it is more likely than not that a gift or transaction of some kind which otherwise appeared regular and lawful was in fact the product of manipulation and exploitation. From my own experience of financial criminal law I would add this, our leading case on dishonesty in fraud is called R v Barton [2020] EWCA Crim 575. It is a case about a deeply dishonest man who ran a luxury nursing home who over many ears systematically defrauded extremely vulnerable elderly people. In his sentencing remarks the trial judge said: "this case is one of the most serious cases of abuse of trust that I suspect has ever come before the courts in this country". He described the defendant as a "despicably greedy man" involved in a "web of deceit and dishonesty." The judge referred the two of the conspiracies involved as "the most brazen I have ever come across". None of that is any surprise to anyone who works in this area of law. I can tell you anecdotally speaking, that it is not unusual in a fraud case to offenders systematically target the elderly. I can also say that these cases are document heavy, difficult to prove and arduous to prosecute. I am quite sure that elderly people are targeted in part precisely because they make poor witnesses and they are generally asset rich easy targets, more so where cognitive decline is involved. Juries in criminal courts can spend weeks, months even, pouring over documents and weighing volumes of evidence to see if a fraud is proved. Undue Influence claims can similarly be laborious to establish. Compare those painstaking, slow, careful, considered exercises if you will with what this bill proposes. Remember the doctor has no power to call for evidence yet all the responsibility of acting as if they had. Considered in that way, you might think this bill hopelessly naïve and this “safeguard” entirely unworthy of that label.

The bill does not have what a lawyer would call a “standard of proof”. This means we don’t know whether a doctor should satisfy themselves on the balance or probabilities that coercion is not involved (i.e. that it is more likely than not). We don’t know if instead the criminal standard is preferred, (that a doctor must be sure). The bill is silent on this. That seems to me an elementary error and an intolerable ambiguity given the subject matter.

Clause 8: The second rubber stamp a week later

By clause 8(3) a person seeking assistance with suicide is granted a whole 7 days after the first rubber stamping procedure to consider their position, some may think that a rather short time. After this point a second doctor must conduct precisely the same declaration as the first and clause 8 proposes that they too must be of the opinion that the person seeking assistance with suicide

I needn’t repeat the points made above in respect of clause 7 because clause 8 is a simply a copy of that clause. As with clause 7 a doctor is asked to form an opinion about a matter with no provision of the necessary investigative or evaluative tools to make such a judgment.

Clause 12: Death by Court Order

Clause 12 purports to regulate the judicial portion of the assisted suicide process, it contains a great many provisions and so my comments will necessarily be extensive. By Clause 12(1), after the second rubber stamping exercise by a doctor is conducted the person seeking assistance with suicide makes an application “to the High Court”.

We have roughly 100 High Court Judges in the UK deployed across the three divisions of the High Court; Family, Chancery and the King’s Bench. Each of those divisions has distinct roles. Divorces and matrimonial disputes go to family, people contesting cases where trusts are involved go to chancery, defamation cases and just about everything else go to the King’s Bench. As is obvious, this bill does not specify a particular part of the High Court for the application it proposes. That seems a strange and unnecessary ambiguity.

It could be said that the “Court of Protection” might be the most natural home for an application of this nature, but that presupposes a declaration authorising a person to secure assistance with suicide has a natural home in the first place. Many consider that this is not the case, among them former President of the Family Division, Sir James Mumby9. In a series of powerful articles on the subject, Sir James argues that “what is proposed is that a judge by court order should facilitate the administration to a patient of a drug intended to bring about the patient’s death. It is difficult to over-emphasise the profound impact of this on what has hitherto been seen to be the proper role and function of a judge.” It may not come as a great surprise to read that the purportedly independent and balanced parliamentary committee considering this bill have declined to hear evidence from Sir James, despite his manifest competence and experience in this area.

By Clause 12(3) the court must satisfy itself that clauses 5-9 have been complied with (that is to say that the relevant declaration and two assessments have been made) and then satisfy itself of the following matters:

There are some rather obvious and serious issues with this because nowhere in the bill do we learn how the court is to satisfy itself of these matters or what sort of evidence it is supposed to be considering. The most the bill will say on this is in clauses 12(4) and (5):

I suspect I need not make the obvious point that Clause 12(4) is positively Delphic in character, “such procedure” is of course undefined and the mix of “must” and “may” in Clause 12(5) simply add to the opacity of what on earth is actually being proposed here. I wish to emphasise this is very unusual in legislation and it risks forcing a number of ambiguities onto the High Court to sort out. These ambiguities are not minor, the High Court is in effect being asked to legislate, particularly insofar as the bill proposes that the High Court should just adopt “such procedure” as is sees fit.

For completeness, Clause 12(6) provides that the court “may” hear from any other person and can order reports on matters (though it unclear what kind of reports are envisaged and nowhere is it said who will fund these or what standard they should meet).

Acknowledging a very great debt to the writing of Sir James Mumby on this topic, I make the following comments generally regarding the court process.

Requiring the court to certify the absence of coercion is fraught with serious difficulties the Division Court identified at length in case of Conway10. In that case the court drew attention to this matter in the following terms (emphasis added)

“the involvement of the High Court to check capacity and absence of pressure or duress does not meet the real gravamen of the case regarding protection of the weak and vulnerable. Persons with serious debilitating terminal illnesses may be prone to feelings of despair and low self-esteem and consider themselves a burden to others, which make them wish for death. They may be isolated and lonely, particularly if they are old, and that may reinforce such feelings and undermine their resilience. All this may be true while they retain full legal capacity and are not subjected to improper pressure by others.”

A decision to seek assistance with suicide is by definition a complex and serious one which could be a product of any number of subtle factors which can be viewed as pressure. In Conway the court emphasised this point in the following terms: “in relation to external pressure exerted by others on the person concerned, the process of seeking approval from the High Court would not be a complete safeguard. The court would have to proceed on the evidence placed before it. External pressures might be very subtle and not visible to the court. For example, it is not difficult to imagine cases of family discussions about money problems, not necessarily intended to place pressure on an elderly relative, in consequence of which they draw their own conclusions that they are a burden and would be better off dead. In any event, it might be difficult to disentangle factors of external pressure from the individual’s own internal thought processes and difficult to tell when external pressure is illegitimate or such as to invalidate the individual’s own choice to die.”

At the risk of repeating myself, the court in Conway said that “The court would have to proceed on the evidence placed before it. External pressures might be very subtle and not visible to the court.” As a matter of common sense, this must be right. Very few people contemporaneously realise they are in controlling and coercive relationships. The very fact of an undue influence claim means that some undue influence has happened, someone vulnerable in some way has already been exploited. Fraud by abuse of position is prosecuted after the crime takes place precise because some plausible dishonest person has succeeded in their nefarious efforts. This means that a person’s declaration in this bill could never be the end of the matter, exploitation can be insidious and the sort of exploitation likely in these cases might be so insidious that it is invisible to the court. That observation should frighten anyone looking at this bill whatever their view of the principle at stake.

Considered in the round, Sir James Mumby made the following observations of this bill which I can’t improve on:

“All in all, in relation to the involvement of the judges in the process, the Leadbeater Bill falls lamentably short of providing adequate safeguards.

Let us consider how an application to the court could be dealt with by a judge in a manner entirely compatible with the requirements of clause 12. The judge could:

Decide the matter without hearing from the patient and with no input of any sort from the patient’s partner or relatives.

Deal with the case in private – in secret – and, if I am right about clause 12(5)(b), without holding any kind of hearing and, moreover, without giving any public judgment.

Adopt a procedure which, beyond whatever little the judge is required to do in accordance with clause 12(5)(b), involves neither testing nor challenging the evidence nor any independent evidential investigation.

In short, an application could be dealt with:

In accordance with a wholly inadequate procedure, and.

Without the public knowing anything about it – not even the name of the judge11”.

It is worth pointing out that some of the work of the Family Division of the High Court involves anxious and difficult cases relating to the welfare of people who cannot make decisions for themselves. You might think in that context that the word of a retired President of the Family Division ought to carry some weight.

Clause 12(8) & (11): Appeal for me, but not for thee

Compare and contrast if you will the following. Here’s clause 12(8) of the bill:

Seems in principle fair does it not? You apply to the High Court seeking assistance with your own suicide, some Judge says no and you think they’ve got it wrong, only fair you can seek a remedy at the court of appeal, no?

Let’s see what happens when we imagine the fact pattern the other way round. You’ve applied for assistance with suicide, a concerned family member thinks you are making a dreadful mistake but a Judge nonetheless grants your application. Surely the concerned family member could appeal that and point to any deficiency or mistake that the Court of Appeal should remedy? Let’s see what clause 12(11) says:

You might consider that an extraordinary thing to see in legislation. I do. Seems to me not to fit with very basic rules of natural justice and fairness and it suggests to me there in reality, there is a single fatal direction of travel in this bill.

The remaining process clauses

By Clause 13, after a period of 14 days a person seeking assistance with suicide makes a second declaration which is identical to the first discussed above. After this point a doctor may assist with suicide according to clause 18 by providing that person with an “approved substance”. As may come as no surprise whatsoever, we have no idea what this substance is to be, how effective it is or what the complication rate is. We know only two things about it, that is both approved and a substance.

Conclusion

I end where I began. Legislating in utopia is easy, for in utopia no one regrets seeking assistance with suicide, no greedy, unscrupulous people ever pressure other people, there is no undue influence or fraud by abusing a position of trust, no one ever coerces anyone or controls them. If by some chance that were to happen in utopia then fear not, because even a local GP conducting their first assessment can spot it. In utopia omniscience and wisdom are common and no court ever makes an error, no wills get rewritten at the last minute and no one ever feels like a burden on others.

By contrast, legislating in the world we actually inhabit is damned hard work. You have to grapple with harsh realities about manipulation and human behaviour. You have to think carefully about what tools to give authorities to root out and detect insidious forms of pressure and coercion. You have to painstakingly define just about every single concept in new laws because laws should be adequately clear and drafted in the knowledge that activist groups will exploit ambiguity. You have to look widely at what financial, social, psychological evidence is and how it might be obtained and deployed. You have to do the job, as an MP of thinking carefully about the quality of the laws you pass.

And that is why this bill is, in my view, an irremediable and dangerous mess. This is a lazy, sloppy text that doesn’t bother to define core terms just as it can’t be bothered with outlining what a court process looks like. Legislating in this fashion on any subject would be below the standards we should expect of our MPs. Legislating in this fashion on this subject is downright reckless.

I’ll have more to say in due course as to (1) the further provisions of the bill particularly the proposed criminal offences and (2) about why there are solid grounds to question the impartiality and fairness of the committee considering this matter.

For the time being, I’ll draw my comments to a close by sending my warmest regards from reality to those happy people who occupy utopia.

For the full text of the bill see https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3774

For criticism of where how one can meaningfully distinguish between some disabilities and the definition of “terminally ill”, see the evidence of Police Scotland to the equivalent Scottish Committee examining this legislation at https://yourviews.parliament.scot/health/ecdded04/consultation/view_respondent?show_all_questions=0&sort=submitted&order=ascending&_q__text=Police&uuId=816173892

For more on this concept and a comparative analysis of how assisted suicide laws have been expanded globally to cover persons with eating disorders, see this excellent blog post by Chelsea Roff - https://blogs.bmj.com/spcare/2025/01/02/could-assisted-dying-for-terminal-anorexia-be-coming-to-the-nhs-by-chelsea-roff/

The other Half’s twitter account is available at @OtherHalfOrg and Chelsea tweets from @ChelseaRoff

https://www.independent.co.uk/tv/culture/esther-rantzen-cancer-update-assisted-dying-b2615481.html

For more on the Mental Capacity Act 2005 generally, see the work of Alex Ruck Keene KC (Hons) available online.

See Clause 36

I won’t detain the reader with clause 6 which is a simple requirement regarding the provision of identity documents when making the first declaration

https://transparencyproject.org.uk/assisted-dying-what-role-for-the-judge-some-further-thoughts/

https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Admin/2017/2447.html

https://transparencyproject.org.uk/assisted-dying-what-role-for-the-judge-some-further-thoughts/

This is a tremendously thorough analysis of deficiencies in the drafting of this Bill. Just a couple of points on clause 12. The threshold to the jurisdiction of the Court of Protection is that someone lacks mental capacity to make a specific decision at a specific time. If so, the Court makes a best interests decision for that person. But an assisted dying declaration would only ever be made by someone with sufficient capacity to do so and make their own decision. So, as Sir James Munby recognised, in the face of some glaring ignorance displayed by lawyer MPs who should have known better, there is not an obvious jurisdiction or template for the role of the High Court envisaged in clause 12. As it stands, that clause falls between two stools: too cumbersome a process for cases where no doubt or question about capacity and free will arises, but too superficial for those where such questions do arise. The public bill committee needs to get to grips with this problem

I have Parkinson's. I'm rather pissed off with Nicolas Mostyn. He used to be a High Court Judge and that may explain why he wants to decide when he should die -- he is a successful individual, used to having a high degree of control over his life, and he wants the same degree of control over his death. Parkinson's runs in my family. I wouldn't have wanted my father to feel he should kill himself to stop being a burden for other family members. I don't want to have to make that decision for myself either.